The story of Gilkerson's Union Giants really begins in 1917. After seven full seasons with the Chicago Union Giants, first as a player, team captain and then manager, Robert Gilkerson parted ways with the historic club after the 1916 season. During his tenure, the Chicago Union Giants had been primarily a touring team and were well-known throughout the Midwest.

The owner of the Chicago Union Giants, William S. Peters, often promoted his club as the “oldest colored team in the Middle West.” At times that claim was extended to include the entire United States. While clearly a bit of promotional exaggeration, the team could trace its origins to the earliest days of Black baseball in Chicago thanks to Peters himself who played for and managed the Chicago Unions (a predecessor to the Union Giants) as early as 1887.

When Gilkerson left the team, he did NOT purchase the Union Giants from Peters or take control of it in any way as is often reported (more on this persistent myth in a later post).

When Gilkerson left the team, he did NOT purchase the Union Giants from Peters or take control of it in any way as is often reported (more on this persistent myth in a later post).

Instead, Gilkerson started his own team along with Union Giants player William “Bingo” Bingham. An announcement published in the Chicago Defender on May 12, 1917 states, “W.L. Bingham blew into town a few days ago with R.P. Gilkerson of Spring Valley, Ill. who has been the traveling manager of the Union Giants, but now owns a team of his own at Arnold Park, Iowa. They are open to all comers.”

This new team would spend most of that summer near popular lake resorts in northwest Iowa, providing entertainment to vacationers. The area would have been known to both Gilkerson and Bingham since the Chicago Union Giants had played a few games there the year before.

The promise of less travel, a familiar location and steady pay likely helped Gilkerson and Bingham convince several of their former teammates to leave Peters’ club and join them in Iowa. This included Jess Turner, Edgar Burch, Clifford White and Hurley McNair.

To many of the Iowans living in the area, Gilkerson’s new team would have looked very similar to the Chicago Union Giants of the year before. So much so that they were often referred to and even billed as the “former Chicago Union Giants.” To add to the confusion, before arriving in Iowa, Gilkerson’s team played a series of games in downstate Illinois and were advertised simply as the Chicago Union Giants.

To many of the Iowans living in the area, Gilkerson’s new team would have looked very similar to the Chicago Union Giants of the year before. So much so that they were often referred to and even billed as the “former Chicago Union Giants.” To add to the confusion, before arriving in Iowa, Gilkerson’s team played a series of games in downstate Illinois and were advertised simply as the Chicago Union Giants.

No mention was made of this being a new team and not the historic team from Chicago. Perhaps this is why so many baseball historians have assumed that Peters must have sold his team to Gilkerson. This however was not the case.

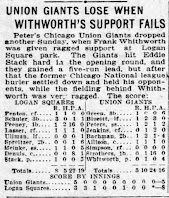

Peters’ Chicago Union Giants fielded a team in 1917 (and for decades after), playing most of their games that year in Chicago, Indiana, Michigan and Wisconsin. The star of that team was Peters’ son, Frank Peters, who played shortstop and occasionally second base. Frank would eventually go on to manage the Chicago Union Giants for many years afterward.

In fact, when W.S Peters was tragically killed in a hit-and-run accident in April 1933, his obituary mentions that his team was entering its 48th season and that his son would carry on with the club. Even after Frank died, the Chicago Union Giants continued on into the 1940’s under the control of Frank Peters, Jr., making it one of the longest lasting semi-pro Black teams in baseball history. A fact that has gone unheralded.

Despite having no real claim to the name of his former team, Gilkerson did not seem to have a problem using it to promote his new team. At times in 1917 and for most of 1919 Gilkerson used “Chicago Union Giants” as his own. Given that he had been so closely associated with the team for so many years, it is unlikely that any opposing teams and managers questioned it. Also, since there was very little overlap in the territories in which the two teams played there were few consequences.

When Gilkerson’s team arrived in Iowa in late May 1917, they adopted the nickname the Lost Island Lake Giants, taken from the area lake where they played most games. According to WWI draft registration cards, several of the players on the team lived in nearby Ruthven, Iowa. When they were not playing at Lost Island Lake, they often played at Arnolds Park which sat at the center of five lakes roughly 30 miles to the north.

In fact, when W.S Peters was tragically killed in a hit-and-run accident in April 1933, his obituary mentions that his team was entering its 48th season and that his son would carry on with the club. Even after Frank died, the Chicago Union Giants continued on into the 1940’s under the control of Frank Peters, Jr., making it one of the longest lasting semi-pro Black teams in baseball history. A fact that has gone unheralded.

Despite having no real claim to the name of his former team, Gilkerson did not seem to have a problem using it to promote his new team. At times in 1917 and for most of 1919 Gilkerson used “Chicago Union Giants” as his own. Given that he had been so closely associated with the team for so many years, it is unlikely that any opposing teams and managers questioned it. Also, since there was very little overlap in the territories in which the two teams played there were few consequences.

When Gilkerson’s team arrived in Iowa in late May 1917, they adopted the nickname the Lost Island Lake Giants, taken from the area lake where they played most games. According to WWI draft registration cards, several of the players on the team lived in nearby Ruthven, Iowa. When they were not playing at Lost Island Lake, they often played at Arnolds Park which sat at the center of five lakes roughly 30 miles to the north.

The Lost Island Lake Giants dominated most Iowa teams that summer. In early August it was reported they had a 21-game winning streak. On August 30, their record was listed at 49 wins, 8 losses and 1 tie with no losses on their home grounds. The team, it was reported, “claim the baseball championship of the state of Iowa and are willing to back the claim against all comers.”

In September the Lost Island Lake Giants entered a tournament in Sioux City during the week of the Interstate Livestock Fair. An article in the Sioux City Journal mentions that they had recently returned from a trip to Minnesota. It also gives their record at 63-9-1 and mentions decisive victories over the Tennessee Rats and American Giants of Chicago.

Over the course of the fair, the Giants beat teams from South Dakota and Iowa to win the tournament on September 20. The newspaper named them “semi-pro baseball champions of the northwest.” It also mentioned the team was headed to Kansas City to play a series with the All-Nations team.

As soon as they left Iowa the team dropped the Lost Island Lake moniker and were once again playing as the Chicago Union Giants. In Kansas City, the Union Giants were scheduled to play Schmelzer’s All-Nations team in a three-game series between September 22-24. According to the only line score found, the Union Giants lost the first game 5-3.

Afterward, both teams quickly left for Topeka, KS where they played another three games series against each other. This is likely how Gilkerson and his team closed their first season.

For additional reading, see the following posts on Gary Ashwill's blog Agate Type, which include more details about some of the players on the 1917 team: Lost Island Giants and Return of the Lost Island Giants.

No comments:

Post a Comment